I read a macro paper about a 50-year market-beating strategy. Here’s my layman’s summary and analysis.

Been doing a lot of reading recently and figured I should share some of the cooler stuff with the Quantbase community. The paper is called A Half Century of Macro Momentum by Jordan Brooks of AQR Capital (all images come from the paper). They’re a quant fund that runs a number of successful strategies. Big caveat here — just because a strategy has beaten the market for 50 years doesn’t mean it will continue to do so. If there’s anything you take away from this article, it’s that there are cool strategies out there that institutions get to profit from, but that oftentimes get deemed too sophisticated for regular investors. That’s a whole nother thing we’ll get into in another blog post, but not today.

Executive Summary (given in paper)

I outline a systematic and diversified approach to global macro investing grounded in economic theory, and detail its performance over the last half century. The analysis shows that the strategy has the potential to deliver strong positive returns, low correlation to traditional asset classes across various macroeconomic environments, and to provide diversification in bear equity markets and rising real yield environments. This systematic global macro strategy appears to be a complement to other alternative risk premia — such as trend-following and long-short value, momentum, and carry strategies — and does not appear to be fully exploited by existing global macro managers.

My Summary (in layman’s terms)

Global macro is a type of investing that involves looking at macroeconomic factors, well, globally. These factors include stuff like unemployment, business cycles, interest rates, international trade, and monetary policy (actions of the Fed and central banks around the world). Global macro investors make predictions based on studying these factors to figure out their outlook for the economy, and invest accordingly. This means their investment universe is much larger than just stocks. They look at long-term government bonds, currencies, and interest rate-affected assets (like short term bonds).

Momentum trading is a strategy that typically involves looking at trends in stock prices and assuming that those trends will keep on going for a short period. For example, if there is upward momentum on a stock, momentum traders want to get in now while it’s still going up. Clearly, this is usually a short-term trading strategy.

In a nutshell, macro momentum is a macro investing strategy that pulls from momentum strategies. Instead of looking at price trends, it looks at macroeconomic trends. It goes long (buys) assets that have positive macroeconomic indicators (explained below) and short (sells) if vice versa. The four asset types this strategy looks at are stocks, currencies, long-term government bonds, and short-term bonds (the paper calls this “global interest rates”). The four macroeconomic indicators this strategy looks at are business cycles (generally, how is the economy doing), monetary policy (what is the Fed doing, is it conservative or aggressive), international trade, and risk sentiment (are stocks going up or down).

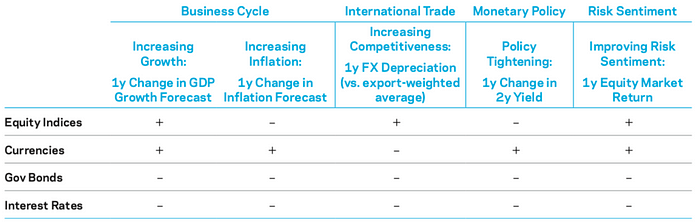

Exhibit 1: Summary of Macro Momentum Indicators

Let’s talk through how I think about this, starting with the column “Increasing Growth.” If the economy is doing well, people have money, so they invest their money into stocks, making the outlook good for stocks. Stocks usually give more of a return than bonds, so their demand goes down, as does their price, making the outlook worse for longer term and shorter term bonds — I’m aware this isn’t the full picture but it’s how I think about it, bond folks please chip in if you’d like to add anything here. Growth is good for currencies as it is accompanied by more business and foreign investment, meaning more demand for the currency — the paper talks about the Balassa-Samuelson hypothesis here, which pretty much says countries with high productivity and therefore prices for tradable goods have higher prices for services too (developed countries vs. developing countries).

Moving to int’l trade, this is captured by looking at whether the currency is depreciating (getting weaker, purchasing power decreasing) on a 1-year basis. Depreciating currency is good for stocks (because our currency is weaker compared to int’l currencies, our goods are relatively cheaper and there’s more demand for them and the companies that sell them), bad for currencies (similar idea to momentum, if currencies have been depreciating, we expect them to continue), and bad for bonds and interest rates. For this last bit, here’s how I think about it — if my currency is depreciating and getting weaker than other currencies, global investors don’t want to be holding it (effectively, its “price” is decreasing). Something that makes a currency attractive is a high interest rate, so parking your money in that currency earns you interest, so a weakening currency’s central bank has less incentive to decrease rates. The price of bonds and other interest rate products increases as rates decrease, meaning this environment/scenario is overall negative for bonds.

Monetary policy, captured by looking at 1-year changes in the yield curve — this is where the x axis is the term of the bond and the y axis is the interest rate paid, it’s usually upward sloping in a good economy and downward in a bad one. If the Fed gets tighter (money printer out of ink), this is bad for stocks and bonds because there’s not as much money to go into these; and it’s good for currencies because it decreases the money supply and increases interest rates (more int’l investment into our currency).

Finally, the risk sentiment is captured by looking at 1-year stock market returns. Increasing risk sentiment is when the stock market has strong returns. This is good for stocks (momentum) and currencies (int’l investment into our stocks), and bad for bonds (who wants to invest in bonds when stocks are doing so well).

Creating a Macro Momentum Portfolio

With this in mind, we now want to create our macro momentum portfolio. This will consist of a long-short portfolio (LS) and a directional portfolio (D) for each combo of indicators and assets. So there’s four indicators times four asset types times two types of portfolios meaning we’ll have 32 “sub” portfolios total that we’ll then combine into the final macro momentum portfolio.

LS — these are market neutral. This portfolio takes a long position in assets with favorable trends (above the average) and short for the assets with unfavorable trends (below the average). Because we’re doing all this with the average in mind, there’s a theoretical neutral exposure to the market, meaning this should perform despite market movements.

D — these take long positions in assets with favorable trends and shorts in assets with unfavorable trends, meaning there’s no computation of an average, and the portfolio can be long or short-exposed.

So we have a LS portfolio for stocks using the economic growth (business cycle) indicator, a D portfolio for the same, an LS for stocks using int’l trade as an indicator, a D portfolio for the same, etc. Once we have the 32 total, he aggregate macro momentum portfolio is created by taking an equal weight across all 32 asset-indicator portfolios.

It’s easy to get lost in the specifics here, so I’ll repeat what we’re doing from a bird’s eye view again. We’re looking at 4 macroeconomic indicators from generally the past year, applying those indicators to 4 asset classes to make a table like the above, and then pretty much using those indicators to predict how the asset classes will perform over the next year. Rebalanced annually.

Performance

This portfolio was tested from Jan 1970 to Dec 2016. That means it’s seen the bear markets of 1987, 2000, and 2008, but not 2020. It’s also seen recessions, wars, stagflation, and disinflation. Here are the results in a table:

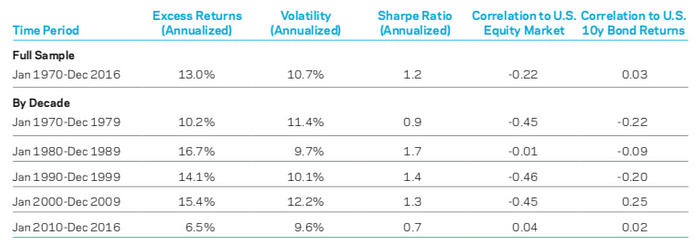

Exhibit 2: Macro Momentum Strategy Performance since 1970

Let’s unpack this. Looks like a consistently market-beating strategy that is un-correlated with the stock and bond markets. One question you might have is, “if this is so good, why doesn’t AQR just invest fully in it?“ The best answer here is probably liquidity — as a fund with ~$150B in assets, it’s impossible to employ your capital all in one strategy without affecting prices enough that you’d no longer be beating markets. Also, AQR’s only been around since 1998, and although I’m sure they had this research in some way or another before the paper was published, it did just come out in 2017.

The table shows a CAGR for the strat (without accounting for inflation) of 13%, compared to 8.41% for the S&P. It beats its composite assets’ returns in rising yield and falling yield markets, in bull runs and bear markets (on average), and has a higher Sharpe Ratio than the S&P for the period (1.2 vs. around 1.0). It’s non-correlated with bonds and has something of a negative correlation with stocks. Does the latter number mean it goes down when stocks go up, meaning it’s gone down for the majority of the period. No. The paper calls the returns of the strategy a “smile” compared to stock returns. Here’s a graph.

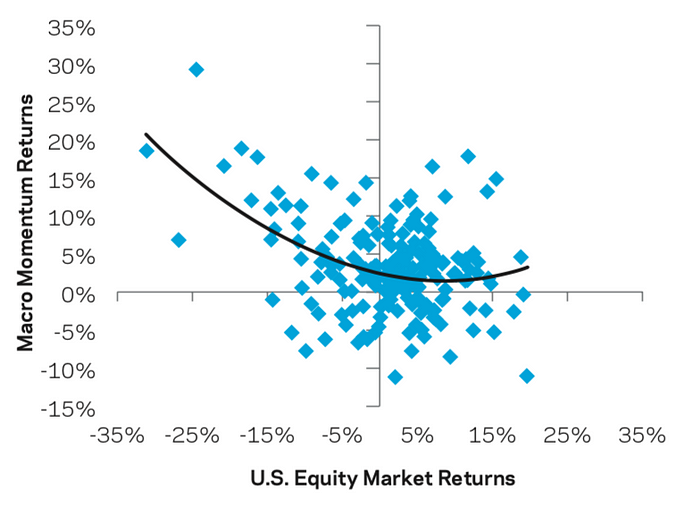

Exhibit 3: Quarterly Returns, 1970–2016

When stocks are up, this portfolio is up a bit too (that’s called a slightly positive beta). When stocks are down, this portfolio is up a whole lot (a very negative beta). On average, the portfolio has a slightly negative beta compared to stocks, as mentioned earlier.

Thanks for reading! We’re making an automated algorithm to track this strategy right now over at Quantbase, so check it out!